This is a summary of a paper by Alessandra Anna Palazzo, an economics graduate student at University of Maryland. She’s on the job market this year, and it looks like she’ll have another paper on Haitian migration to Chile, so keep an eye on her!

Chile has been a major destination for Haitian labor since 2017, when 105,000 Haitians entered the country. I wrote about this in a previous post, showing this graph of how remittances from Chile grew rapidly. Clearly, since they are sending money home, these migrants are working. What, then, has been their effect on Chilean firms?

A recent paper presented at the North East Universities Development Consortium (NEUDC) 2024 conference looks at how firms responded to the Haitian migrants. But it doesn’t look exclusively at them. During these years, Chile had a large influx of migrants, and the 100,000+ Haitians wasn’t even the largest group. There were also hundreds of thousands of Venezuelans escaping the humanitarian crises that led to its rigged election.

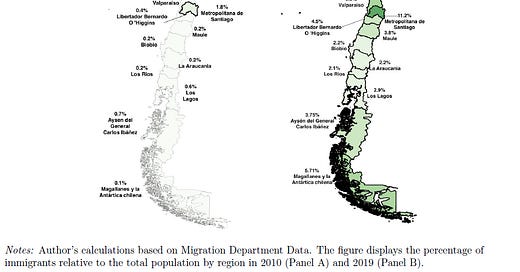

This was a significant shock to Chile. Unlike Argentina or Brazil, Chile historically was not a major destination for immigrants, not least because the Andes acted as a natural barrier to entering the country. As a result, the share of migrants in the population moved from around 2% to 11%. And instead of just hitting historical hotspots, the migrants spread throughout the country. The figure below shows that the southern-most region of Chile went from 0.1% immigrants to 5.71%.

Haitians were a significant contribution to those increases in migrants, but even more so were the Venezuelans. Below is the annual flows of migrants by country. What surprises me is that the Haitian and Venezuelan migrants track each other step for step up to 2016, begin to diverge in 2017, and then the Haitian migration peaks and falls while Venezuelan migration continues to climb. This early peak for Haitians was because the Chilean government changed visa requirements. Previously, Haitians could enter for 90 days with a tourist visa acquired at the border and apply for a work visa while already in the country. The government changed the visa rules to require Haitians to get a visa from the consulate in Haiti before coming to the country. (It also did that for Venezuelans later on, but I think it’s interesting that the Haitians were targeted first when inflows were similar.)

A key feature of this paper is that the education levels of the migrants were different. In the next figure, the authors show the share of immigrants who did not have a college education. Haitian immigrants during this post-2016 boom were overwhelmingly unlikely to not have a college education: over 90% had less than a college education. The Venezuelan migrants, on the other hand, had much higher education levels. Over 50% had a college education, and in some waves it was close to 70%.

The crux of their analysis is to look at how the immigrants’ education levels affected firms. A flood of high- and low-skill labor comes to your country. How does that affect competition with native labor?

The authors address this question by calculating the elasticity of substitution between native and immigrant labor. The elasticity of substitution measures how sensitive firms are to their input costs. If immigrant labor is cheaper, then firms may use more immigrant labor than native labor, but that change will depend on how well one can replace the other. For example, if an immigrant comes to the hospital looking for work, it is probably easy to get him a job as a janitor, but it’s much harder to get him a job as a doctor. Even if the immigrant was a doctor in his home country, the hospital might be reluctant to hire him over a native doctor because there are differences in language, culture, and certifications. How substitutable were native and immigrant labor in Chile?

Their estimates for the elasticities of substitution are in the table below. They calculate two elasticities: one for unskilled labor and one for skilled. As expected in the little thought experiment, it’s much easier to replace unskilled native workers with unskilled immigrants than it is for the skilled. But the table hides a fascinating result.

While the paper identifies skilled and unskilled based on their education, it’s highly correlated to the origin country. The increase in unskilled labor is coming mainly from Haiti while the increase in skilled labor is coming from Venezuela. So we can squint at these elasticities and say that the unskilled elasticity is really “How easy is it to replace a Chilean with a Haitian?” And the skilled elasticity is really “How easy is it to replace a Chilean with a Venezuelan?” Firms are much more willing to replace their Chilean workers with Haitians than Venezuelans.

The most interesting part of this, in my view, is the language barrier. If an English college grad came to the United States, I would see him as a perfect substitute for an American college grad. Sure, he puts u’s in words that don’t need them, but overall the work should be comparable. In my mind, Venezuelan college grads should be on similar footing as Chilean college grads. Not the same culture, but the education and language barrier should be small. Haitians, on the other hand, speak a different language. Sure, some are coming with basic Spanish, but these are going to be like the Mexican workers coming to the US, and probably inspiring similar frustrations in Chile (“¿Por qué vienen a un país donde no hablan la lengua?”). Yet they are much more interchangeable with unskilled Chilean workers.

While the Haitian results are interesting, I guess my main takeaway is the shock that Chilean college graduates are harder to replace with Venezuelans. The authors don’t explore this aspect, but I hope they will.

Would be interesting to know if the skilled workers category can be broken into (1) skilled workers with necessary higher academic credentials (doctors, lawyers, teachers, architects); and (2) skilled workers without such necessary higher academic credentials (plumbers, electricians, carpenters, skilled appliance repair workers, machine operators). The skilled worker elasticity of substitution might be lower (I hypothesize) because skilled workers are more able to defend their interests than are « unskilled » workers (cleaners, drivers, gardeners, domestics, food service workers) and more able to exclude entry from Venezuelans and other foreigners with similar, but not exactly the same, credentials.

Thank you for covering this topic. I lived in Chile for some time. In fact, i consider the country my second home. It was interesting to witness the influx of Haitians and Venezuelans into the country. A little surprised about the influx of people into the South.