Venezuela is in the middle of an election crisis. I happen to have published a paper on similar election concerns in Haiti. So I decided to do analyze the Venezuelan data.

I was surprised no one is talking about what I found.

Of course, we need to acknowledge that the real talking point is that Venezuela's president, Nicolas Maduro, is blatantly stealing an election. Analyzing the election data feels like walking into a police investigation of a stolen car, pointing to the odometer, and saying, "Not only did they steal the car, they drove it!"

But there are still useful lessons from looking at the voting data. After all, Maduro and his defenders claim that the data circulating are "presumably false." If it's real data, is there any evidence from the data that the election data is false? Is there any evidence of interference in the election?

I'll present some evidence that the election results do show evidence of tampering. But this manipulation was in favor of Maduro, not González. Thus, the election underrepresents the true support for the opposition.

Where are the data from?

When Maduro claims he won the election, he's doing so without presenting any evidence to back his claim. Well, he has reported one statistic. He claims he got 5,150,092 votes, the leading opposition candidate, Edmundo González, received 4,445,978, and everyone else got 462,704. Therefore, he won with 51.2% of the vote. But he hasn't reported any data to show where he won those votes.

The opposition, however, brought receipts. Literally. Venezuela's election allows monitors from each party to be present at voting stations. During the day, the monitors are meant to keep parties from manipulating the election. At the end of the day, they receive a tally of the votes.

In preparation for the election, the opposition held weeks of training to make sure they safely acquired the vote tallies.

Tens of thousands of volunteers participated in training workshops nationwide in recent months. They learned that under the law they could be inside polling centers on Election Day, stationed near voting machines, from before polls opened until the results had been electronically transmitted to the National Electoral Council in the capital, Caracas…

The 90,000 party representatives were taught to obtain a copy of the tally sheets — printed from electronic voting machines after polls close — before the results were transmitted to the council…

The volunteers were also trained to use a custom-made app to report voting center irregularities such as opening delays or power outages, and to scan a QR code printed on every tally sheet.

The opposition has now posted the vote tallies online. Anyone can browse the data at from the level of the state down to the voting machine.

Are the data real? Indisputably. This is exactly the process that the law put in place over two decades ago.

The question is, does the data show evidence of fraud?

Searching for Fraud

It is incredibly hard to make definitive claims about fraud using only voting data. It's nearly impossible with just the final tally. Maybe you could say that a really high vote share indicates fraud. But how high is too high? If I told you that a candidate won with 73% of the popular vote, would you believe that it was fair? That's the share of the popular vote that Thomas Jefferson got in 1804.

And Maduro isn't even claiming he won with a mandate. He's saying he eked out 51.2% of the vote. That's higher than the share George W Bush got in 2000 and what Bill Clinton got in both 1992 and 1996. Seems like a reasonable vote share.

Even though it's hard to use vote shares to detect fraud, some have tried. Terrence Tao (as in THE Terrence Tao, greatest living mathematician) did some calculations on the probability that Maduro got exactly the votes he claims. Using Bayes’ theorem, Tao concludes that it's highly unlikely that the vote distribution would land exactly as it did without some manipulation.

We can get more mileage out of disaggregated data. At a higher resolution, we can look for irregularities. But it's still not certain. That's because tons of weird election patterns can be rationalized in different settings. A Republican winning 49 out of 50 states sounds suspicious today, but it's exactly what Ronald Reagan did in 1984.

We can get the most evidence when we combine the data and a little bit of economic intuition. If we have disaggregated voting data, what would be the signs of manipulation? To get at that, we have to think about how someone manipulates an election at the ground level.

One common tactic is ballot stuffing. You shove a bunch of votes for your preferred candidate into the box, or if the voting machines don't actually take a physical ballot, it amounts to spamming the machine with a candidate. From the perspective of data analysis, ballot stuffing creates a really nice statistical relationship. If I add 100 votes for Maduro to the box, then his vote share increases. But that also looks like 100 more voters showed up, so turnout increases too. Ballot stuffing creates a positive correlation between turnout and vote share.

Another tactic is voter intimidation. This involves preventing the opposition from voting against you. Like with ballot stuffing, this creates a nice statistical relationship, but it’s not as mechanical. Voter intimidation is likely to happen in areas where support for the opposition is high. That means in areas with low support for you, you’ll create low turnout. That means voter intimidation creates a positive correlation between turnout and vote share.

This is super convenient. Two of the most common ways to manipulate an election create the same correlation. If the election shows a positive relationship between turnout and vote share, that is some evidence towards manipulation.

But let's highlight why this is not a foolproof test. Suppose you had a Black candidate for president, and neighborhoods have varying degrees of racial mixing. If the Black candidate was effective at mobilizing Black voters, then we would see both higher turnout in Black neighborhoods and higher support. The positive correlation exists without any manipulation.

With that caveat in mind, let’s explore Venezuela’s data along with some comparison elections. After getting a sense of what the correlation looks like, we’ll use some economic reasoning to generate a finer test of the hypothesis.

Election Fingerprints

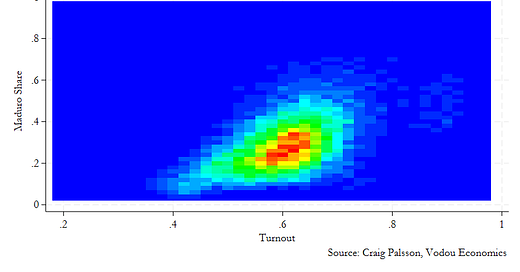

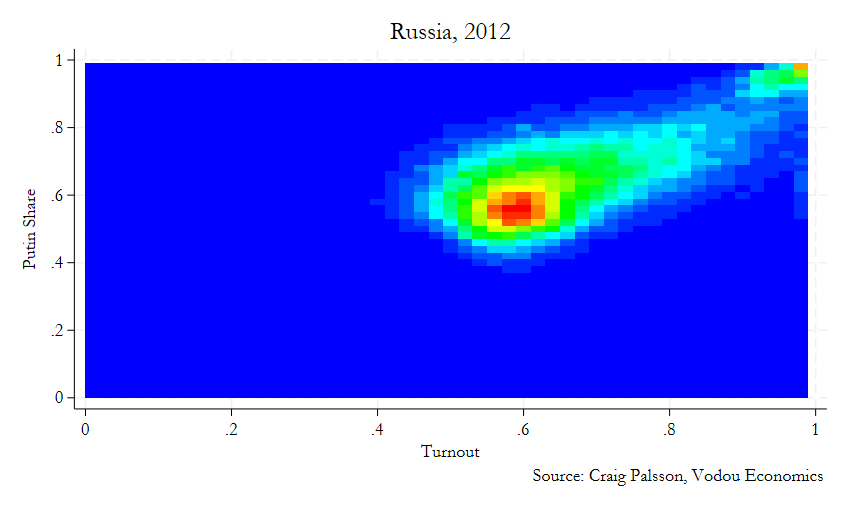

I’m going to create heatmaps for three elections: Spain in 2008, Russia in 2012, and Venezuela in 2024. The idea for heatmaps comes from Klimek et al. (2012), though they call them “election fingerprints.”

First, we have Spain in 2008. This is an example of a free and fair election. This is reflected in the heatmap: there’s a concentration of results around 80% turnout and 40% of votes going to the winning party, and it diffuses evenly from there.

Next, we have Russia in 2012. Putin won by a landslide, but there were all sorts of problems around the election, including video evidence of ballot stuffing. Looking at the Russia heatmap, we can see that there’s a concentration of votes around 60% turnout and 50% support, but that the results smear up to the top-right corner. In fact, there’s a second heat center where many voting stations reported both 100% turnout and 100% support for Putin. This is the positive correlation we expect from ballot stuffing.

Finally, let’s do Venezuela in 2024. It’s missing Russia’s obvious signs of ballot stuffing, even though there is some drift towards the top right corner. But it also has a smear towards the bottom left: locations with high support for the opposition also had low turnout. That’s a pattern consistent with voter intimidation.

I would label this as “between Spain and Russia.” But that’s a pretty obvious conclusion. Imagine Maduro manipulated the election as much as Putin did but still lost. His ability to manipulate the grassroots political environment is weak, which is why he has to go for the outright steal.

A Finer Economics Test

Like I said, there are other reasons why we would expect to see a positive correlation between turnout and Maduro’s vote share. This is where we need a little more economic reasoning. What are the constraints on manipulating the election?

First, Maduro is clearly constrained on resources for stuffing ballots and intimidating voters. If he had sufficient resources, he would have pulled a Putin.

Second, there are travel constraints. There are only so many locations your goons can travel.

Finally, all votes are equal. Since the election is based on the popular vote, not something like an electoral college, then a vote is the same no matter where it's cast.

Combined, this tells us that goons are probably going to work in a few locations. They probably don't need to hit every polling station in a region. They just need to choose one or two and manipulate those.

That ends up being great for trying to test for manipulation. The “Black neighborhood” effect I cited above makes the point that there are systematic differences across locations that might influence both vote share and turnout. For instance, parishes may have specific demographic, geographic, or political characteristics that can affect voting behavior and outcomes. But if we compare voting booths within the same parish, that removes the variations caused by factors at the parish level. In theory, this should handle most of the differences across booths because factors like population size, socioeconomic conditions, and political leaning that might differ across locations are absorbed by comparisons. If you still observe a strong relationship between vote share and turnout, it implies that the relationship isn't simply due to the inherent differences across locations. Instead, it suggests that there may be something unusual happening at the booth level, such as manipulation.

The test, then, is to see if the positive correlation persists even once we control for finer and finer geographic regions. It’s like saying, “Does this voting station look weird even once we account for it being in a Black neighborhood with high turnout and high support?” In econometrics terms, this means we want to see if the positive correlation survives adding various levels of fixed effects.

What do the data say?

Without doing the finer controls, the regression shows a positive relationship between Maduro’s vote share and turnout. Moreover, it shows that a 10% increase in turnout is associated with a 14% increase in Maduro’s vote share. That relationship remains stable as we include finer and finer geographic controls. Even when we control for the parish where the votes are located, where we’re basically controlling for the “Black neighborhood” effect, we find the relationship is stable.

The only time we make a dent in it is if we control for the station where the booths are located. Within each station, voters are assigned to tables. Each table oversees voter eligibility, and it is at the table level that they report the votes. Votes and turnout across tables should be pretty similar, and if there was voter intimidation, it should affect all of the tables the same. So at this level, we should see the effect disappear. Consistent with that prediction, we do see most of the effect vanish. But there’s still a positive, significant relationship. This could mean that even within stations, there was some ballot stuffing across tables.

If you want the full results, I have them below.

Final Thoughts

Like I said at the start, this analysis is more straining over gnats than it is dealing with the camel of a stolen election. But it highlights how Maduro tried to manipulate the election. The evidence shows strong support for voter intimidation and some support for ballot stuffing. But he’s not as competent as Putin, and he failed.

It also highlights that, in results that show strong support for the opposition, the true support is even higher. It strengthens the case for pushing for Maduro’s removal. And it highlights that the only thing keeping him in power is the handful of people clinging to the rents they get from his regime.