After the assassination of Haiti’s president and a significant earthquake in Haiti’s southern peninsula, the logical next step seemed to be thousands of Haitians trying to enter the U.S. Haiti is in shambles; of course people want to escape.

So not very many people were surprised when 30,000 Haitians arrived in Del Rio, Texas. But they should be surprsied! This is clear from the weirdest part of it: it happened in Texas!!

Instead of a tide of refugees washing up on the shores of Florida, we had thousands of Haitians sleeping under a bridge 300 miles inland. Instead of images of the Coast Guard turning back shoddy boats, we got pictures of mounted police with whips.

While it seems like this migrant crisis started in July 2021, it actually started over 10 years ago with the first earthquake. It has very little to do with current events in Haiti and more to do with U.S. immigration policy. And Jacqueline Charles has been ahead of this story for years. So I’m going to synthesize her work and add important economic details.

First, to understand Texas, we have to go to California.

California

California shows us that this migrant crisis is much older than we might think and that the U.S. already had policies in place to deter it. Then at the end I’ll show you how this crisis was likely triggered by a change in policy in May 2021.

It’s 2016. An election is on the horizon, and while Americans know the next president is going to be Hillary Clinton, some Haitians are doubting. Looking at the political landscape, they see the potential for a Trump presidency. And he’s surfing the political wave on a board built on immigration restrictions. So Haitians start arriving at California.

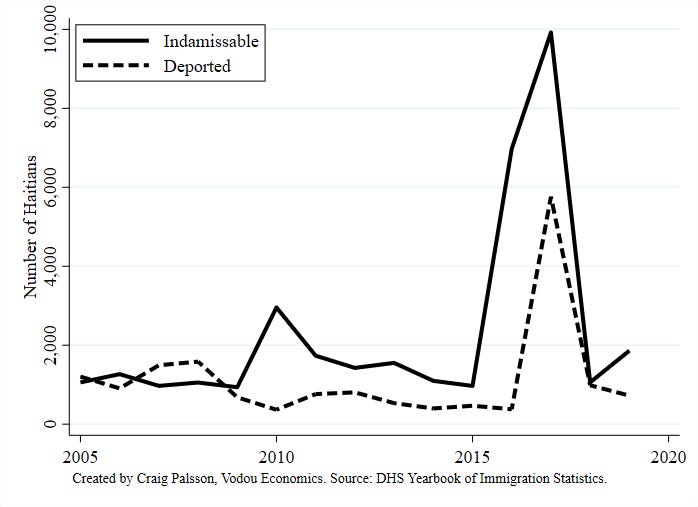

Using data from the DHS Yearbook of Immigration Statistics, below I’ve plotted the number of inadmissable aliens from Haiti (i.e. applied for legal migration but were rejected) and the number of aliens removed (re: deported) to Haiti. Note how the earthquake in 2010 created an uptick in inadmissable migrants, but it looks like Kevin Hart standing next to the Dwayne Johnson-sized wave of 2016/2017.

This influx of migrants did not catch the Obama administration by surprise. These Haitians were on a long trek through Latin America, and waypoints sent the White House warning in advance. In response, the Obama administration reversed its policy on not deporting Haitians, established in 2010 after the earthquake. Allegedly, the change came because Haiti had been deemed safe again. But this was as sincere as my daughter saying she’s not that hungry when she sees we’re having broccoli cheddar soup for dinner. The administration saw a wave of migrants moving through South/Central America, and they acted to deter it.

So we’ve seen this migrant wave before. But how in the world did they end up in California, the absolute farthest entry from Haiti?

South America. It’s like America, but South.

If there was an Olympics for suffering, Haiti would regularly make the podium. And it turns out the Olympics have more to do with these migrant waves than the most recent suffering.

After the 2010 earthquake, Haiti was devastated. There wasn’t much opportunity. So Haitians looked elsewhere. They found Brazil.

Haitians 10 years ago could see Brazil’s economy was in a good spot. There was decent opportunity across a range of skills. And it helped that Brazil’s President Rousseff was actively recruiting Haitians to work in the country.

Much of the opportunity in Brazil stemmed from two major events on the horizon: the 2014 FIFA World Cup and the 2016 Olympic Games. Preparing for and executing these events requires a lot of labor, and host countries frequently pull on migrant labor to fill gaps. For instance, next year’s World Cup in Qatar has relied heavily on migrant labor, leading to thousands of migrant deaths.

But as the 2016 Olympic flame was extinguished, so was labor demand. Opportunity dried up. And this is why we saw the influx of Haitians in California. Instead of coming directly from Haiti, they had passed through Brazil and were now looking for their next job opportunity. When the Obama administration shut the doors, where could they go instead?

Chile.

In 2017, 105,000 Haitians traveled to Chile. That’s about 1% of Haiti’s population, and an even greater share of the able-bodied labor force. The migration shock to Chile has been much larger than Brazil, as evidenced by the remittances sent from each country back to Haiti.

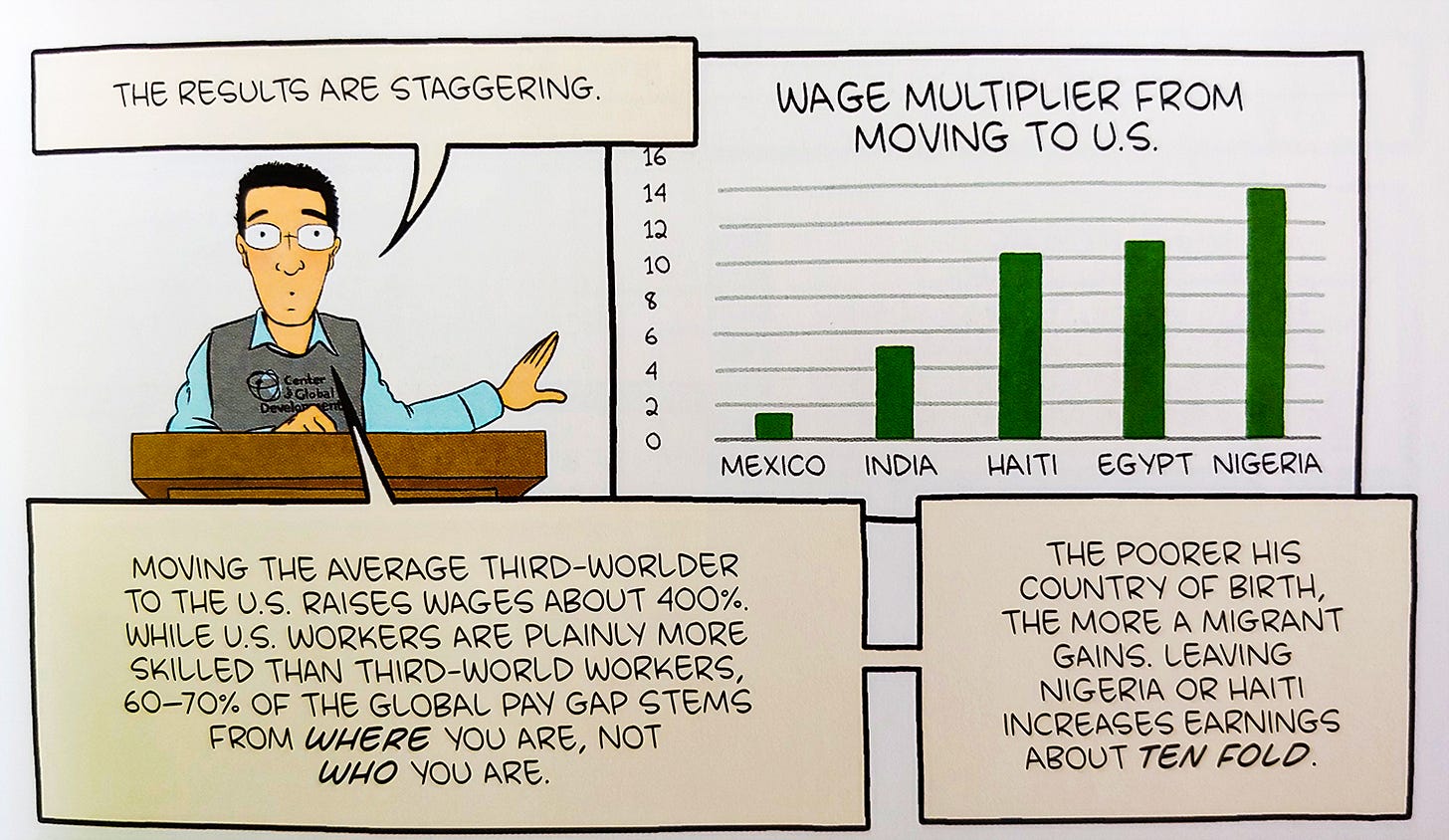

We shouldn’t be surprised that workers are leaving Haiti. The gap between Haiti and other countries has been wide for a long time. One famous study by Michael Clemens, Claudio Montenegro, and Lant Pritchett found that moving a Haitian to the United States would lead to a 10x increase in the worker’s wages. The finding is so shocking it was immortalized in Bryan Caplan’s Open Borders.

But that study was published in 2009 and it was for migration to the U.S. That same study found that a Chilean could move to the United States and increase his wages by 3.5x. With those figures, a Haitian moving to Chile would be lucky to triple his wages.

Now Haiti’s economy has declined so much that the wage gap has become a wage chasm, and Chile is the new U.S. Although we’re still waiting on the data, Jacqueline Charles’s reporting describes the economic boon of moving to Chile. One Haitian migrant got the 10x increase you would expect from moving to the U.S.:

In Chile, he works six days a week at a furniture factory in Casablanca, an hour drive northwest of Santiago. He makes around $800 a month — a vast sum compared to the $78 a month he earned in Cap-Haïtien in a tourism job tending to vacationing tourists. The salary couldn’t even cover school fees for his three children.

But some are even getting wages in Chile 20x their wages in Haiti:

Casseus’ $747 monthly salary, before taxes, is more than the $540 budget he had for the entire staff at the school in Haiti — 19 teachers plus support workers. But it comes at a steep price: He works 60 hours a week, leaving little time for social activities or Spanish classes, a necessity for a better job.

It’s no wonder Haitians are leaving!

But why the U.S.?

If things are going so well in Chile, why are 30,000 Haitians knocking on America’s southern border?

First, the Chilean dream is turning into a nightmare. Unsurprisingly, mass migration has led to xenophobia in Chile. With COVID-19, work is getting harder to find, and legal work even harder.

But another drawing factor is probably a change in U.S. policy.

Back in 2010, following the earthquake, the U.S. granted Haitians already in the United States Temporary Protected Status (TPS). This means that even if you arrived in the United States illegally, or if your legal status had expired, the government will not deport you while the status is active.

The key to TPS is that it is granted to only migrants currently living in the country. If it was given to any citizen of the country, then it would provide a massive incentive to new migration as it effectively opened the borders. The problem is that this requirement is not often communicated to the community. In Haiti, I’ve talked with well-educated Haitians who mention they see friends leave for the U.S. trying to get TPS.

The joke in the immigration community, however, is that TPS is never temporary. There are Somalians who have been under TPS since 1991. It’s rare for the government to revoke this status. As unexpected as the Spanish Inquisition, the Trump administration looked at ending TPS, stressing the “temporary”.

With Trump’s loss, TPS did not end. In fact, it was expanded. In May, Biden, probably remembering the earthquake during his tenure as Vice President, extended TPS and expanded it to include all Haitians who had come before May 21, 2021. All of those Haitians who came to the U.S. thinking they could get TPS actually got it!

This puts those migrants who went to Chile in a funny position. They avoided the U.S. because they knew policy for Haitians had become unwelcoming. Yet that choice in retrospect was terrible because they lost an opportunity to get TPS. So what are they thinking today?

Obviously, it’s time to finally get to the U.S.

And that’s how we get 30,000 Haitians sleeping under a bridge in Texas.

Thanks for the post! It's interesting but this doesn't really answer the question posed. Why did they end up in Texas instead of California (or any other state)? Land crossing from Chile all the way to the US involves multiple border crossing plus hopping a canal. Are they truly making that journey? Or, if not, are they flying to Mexico then crossing at the closest border? Is that because of Mexican visa policies? The TPS policy explains the surge, but I'd love to learn more about the logistics

*they weren't whips